Wednesday, 13 April 2022

D&D Monsters: Couatls

Wednesday, 6 April 2022

D&D Monsters: Beholders

1E

Thursday, 17 March 2022

D&D Monsters: Otyughs

Wednesday, 2 March 2022

D&D Monsters: Ropers

The roper is another of the "does what it says on the tin" monsters that are original to D&D. Alongside such creatures as trappers and piercers, it's clearly intended to disguise itself as part of the background and attack unexpectedly but does have a more distinctive look and an unusual method of attack that make it more memorable than they are, with the result that it consistently appears in the core Monster Manual books of each edition.

The roper is another of the "does what it says on the tin" monsters that are original to D&D. Alongside such creatures as trappers and piercers, it's clearly intended to disguise itself as part of the background and attack unexpectedly but does have a more distinctive look and an unusual method of attack that make it more memorable than they are, with the result that it consistently appears in the core Monster Manual books of each edition.1E

Wednesday, 16 February 2022

D&D Monsters: Mind Flayers

1E

Monday, 24 January 2022

D&D Monsters: Umber Hulks

1E

5E

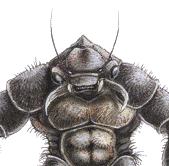

It's with the head that this most seems to break down. Even so, it's notable that the jaws hinge horizontally, as they do in vertebrates, and each possesses triangular teeth, something they don't do in insects and the like. Countering this we have the "mandibles" which have no clear counterpart in any real-world vertebrate - they don't seem to be tusks like those of an elephant, for example. Thus, while it's plausible that there is a bony skull underneath the chitinous head-sheild, and one complete with a lower jaw, there must also be some major modifications.

It's with the head that this most seems to break down. Even so, it's notable that the jaws hinge horizontally, as they do in vertebrates, and each possesses triangular teeth, something they don't do in insects and the like. Countering this we have the "mandibles" which have no clear counterpart in any real-world vertebrate - they don't seem to be tusks like those of an elephant, for example. Thus, while it's plausible that there is a bony skull underneath the chitinous head-sheild, and one complete with a lower jaw, there must also be some major modifications.Wednesday, 19 January 2022

D&D Monsters: Devils

In regular English, the term 'devil', when not applied specifically to Satan, is essentially synonymous with 'demon'. Whereas the word 'demon' originally had a more benign meaning, 'devil' has always meant an evil entity, and now typically means one that is specifically part of the Christian mythos even if the general concept exists in other religions, too.

In regular English, the term 'devil', when not applied specifically to Satan, is essentially synonymous with 'demon'. Whereas the word 'demon' originally had a more benign meaning, 'devil' has always meant an evil entity, and now typically means one that is specifically part of the Christian mythos even if the general concept exists in other religions, too. In D&D, however, devils are distinct from demons, making up the organised legions of Hell rather than being rampaging creatures of malevolent chaos. In 1E, six main types exist, although other common ones have been added since, all fitting within a defined hierarchy where weaker devils can (with difficulty) be promoted to higher ranks at the whims of those even higher up the chain. Compared with the demons, these six standard types are more likely to owe their origins to myth or at least to traditional depictions of such beings, rather than just being odd combinations of animal parts.

Sunday, 2 January 2022

D&D Monsters: Erinyes

Some versions of the myths state that there are only three Erinyes, but others are much vaguer about the numbers. Notably, the three named Erinyes stand guard over the City of Dis surrounding the Sixth Circle of Hell in Dante's Inferno. It may be this that inspired their adoption as a type of "devil" in D&D, although they (and Dis) are moved to the Second Circle in the 1E Monster Manual, befitting their status as the weakest of the true devils in that edition. Something of a demotion from their mythic origins, then.

Sunday, 26 December 2021

D&D Monsters: Demons

Given that "demon" is such a broad term in real-world mythology and religion, there are inevitably many different interpretations and forms of the beings. They were included in D&D right from 0E, where they are listed simply by a numbered type, increasing in power from one to six. Alternative names are provided in 1E, which become the standard names from 2E onwards. Notably, 2E also tried to pretend that they weren't really "demons", lest that offend anyone religious, and described them instead using the invented word tanar'ri. 3E switched back to "demon" again, explaining that the "tanar'ri" were merely a common subtype; the latter term has largely been deprecated since. 5E restored the numbered type sequence, but only as rarely-used categories of increasing power so that, for example, chasme mosquito-demons are now another example of Type 2 demons, alongside the original hezrou.

Given that "demon" is such a broad term in real-world mythology and religion, there are inevitably many different interpretations and forms of the beings. They were included in D&D right from 0E, where they are listed simply by a numbered type, increasing in power from one to six. Alternative names are provided in 1E, which become the standard names from 2E onwards. Notably, 2E also tried to pretend that they weren't really "demons", lest that offend anyone religious, and described them instead using the invented word tanar'ri. 3E switched back to "demon" again, explaining that the "tanar'ri" were merely a common subtype; the latter term has largely been deprecated since. 5E restored the numbered type sequence, but only as rarely-used categories of increasing power so that, for example, chasme mosquito-demons are now another example of Type 2 demons, alongside the original hezrou.Wednesday, 22 December 2021

D&D Monsters: Vrocks

The word "demon" comes from Ancient Greek where it was used to describe semi-divine beings and generally lacked the negative connotations of the modern word. Early Christians later co-opted it as a term for "servitors of foreign/hostile deities", from which it rapidly morphed into something more explicitly evil. In that sense, it's a common concept in many real-world religions, a generic term not linked to any one in particular and that therefore fits with the typically polytheistic worldview of D&D.

The word "demon" comes from Ancient Greek where it was used to describe semi-divine beings and generally lacked the negative connotations of the modern word. Early Christians later co-opted it as a term for "servitors of foreign/hostile deities", from which it rapidly morphed into something more explicitly evil. In that sense, it's a common concept in many real-world religions, a generic term not linked to any one in particular and that therefore fits with the typically polytheistic worldview of D&D.The vrock specifically has no direct antecedents in mythology or in Christian demonology. It may be partly inspired by the demonic Tash from C.S. Lewis's Narnia books, but the resemblance isn't that strong and could be coincidental. Vultures appear in the myths of both African and American cultures since similar birds live on both continents. (In reality, the "vultures" on either side of the Atlantic are not closely related, despite their physical similarity, but this may not be relevant in a fantasy world).

Friday, 26 November 2021

D&D Monsters: Nagas

Nagas originate in Hindu mythology, in which they are magical beings that can take on various snake-like forms. Some appear as literal snakes and, indeed, the scientific name of the main cobra genus is Naja, based on the Sanskrit word for 'cobra'. Similarly, it's no coincidence that the feminine form of this word is "nagini" - although the exact English spelling can vary.

Nagas originate in Hindu mythology, in which they are magical beings that can take on various snake-like forms. Some appear as literal snakes and, indeed, the scientific name of the main cobra genus is Naja, based on the Sanskrit word for 'cobra'. Similarly, it's no coincidence that the feminine form of this word is "nagini" - although the exact English spelling can vary.Often capable of shape-shifting, mythic nagas can take on fully human or partially humanoid form, with the latter more usually resembling the yuan-ti and mariliths of D&D than the shape seen in the game (although this is not unknown). Nagas are generally said to be righteous, if not exactly benevolent, and are often set to guard the treasures of the gods, hence at least the 'guardian nagas' of D&D.

Wednesday, 17 November 2021

D&D Monsters: Sphinxes

The sphinx is a creature of Greek myth, taking the form of a winged lion with a human face. In the original myths, she is, like the minotaur and many others, a unique creature, and appears most famously in the story of Oedipus.

The sphinx is a creature of Greek myth, taking the form of a winged lion with a human face. In the original myths, she is, like the minotaur and many others, a unique creature, and appears most famously in the story of Oedipus. Confusingly, however, the term was retrospectively employed (possibly by the Greeks themselves) to also refer to the wingless lion-bodied statues of Ancient Egypt. These aren't the same thing as the Greek monster, and it isn't known what the Egyptians actually called them. They were usually, but not always, male and, judging from the statuary, were probably perceived as good and noble beings, unlike the much more hostile Greek creation.

It seems to be the case that, in D&D, the male or "androsphinx" was based largely on the Egyptian creature (albeit with the addition of wings), while the female or "gynosphinx" has closer links with the Greek version.

Tuesday, 26 October 2021

D&D Monsters: Lamias

At some point between then and medieval times, lamias change again, keeping their powers of sinful seduction, but now becoming part-serpent - physically resembling the yuan-ti of D&D. In fact, outside of gaming, this may remain the most common depiction. In the 17th century, however, an alternative description made them quadrupedal, a scaly hooved creature with a woman's head and breasts. This, combined with a desexualised version of the seduction powers, seems to be the likely inspiration for the game version.

Wednesday, 13 October 2021

D&D Monsters: Dragon Turtles

1E

Wednesday, 22 September 2021

D&D Monsters: Metallic Dragons

In European myth, dragons are almost universally regarded as evil - rapacious monsters that lay waste to the countryside, have to be slain by heroic knights and, in many cases, essentially breathe hellfire. They are, sometimes literally, diabolic creatures. The same is not necessarily true in other cultures, such as that of China, where dragons may not necessarily be easy to parlay with or recruit as allies, but aren't fundamentally hostile, either.

In European myth, dragons are almost universally regarded as evil - rapacious monsters that lay waste to the countryside, have to be slain by heroic knights and, in many cases, essentially breathe hellfire. They are, sometimes literally, diabolic creatures. The same is not necessarily true in other cultures, such as that of China, where dragons may not necessarily be easy to parlay with or recruit as allies, but aren't fundamentally hostile, either.In D&D, the good counterparts to the evil chromatic dragons are, of course, the metallic ones. Indeed, they are among a relatively small number of 'good monsters' to make it consistently through into the core books of later editions. Up until 5E, they are portrayed as rarer, but individually more powerful than, the chromatic dragons. They are perhaps even rarer in games than they are usually described as being in the universe (in two campaigns of Critical Role, the PCs have so far encountered at least seven chromatic dragons, and only one metallic). Doubtless, this is because they are less useful in a typical game if you're not going to fight them - and they're too powerful to be regular allies.

Saturday, 4 September 2021

D&D Monsters: Blue Dragons

A considerable number of mythological deities are said to throw thunderbolts - Zeus and Thor are merely the most familiar of these to Europeans, with examples known from many other cultures. Actual mythic creatures that throw lightning, however, are much less common, although Chinese dragons are at least associated with thunder and storms. In D&D, however, it seems an obvious attack mode once we've dealt with fire and ice, and, naturally enough, it's associated with the dragon that's the colour of the sky.

A considerable number of mythological deities are said to throw thunderbolts - Zeus and Thor are merely the most familiar of these to Europeans, with examples known from many other cultures. Actual mythic creatures that throw lightning, however, are much less common, although Chinese dragons are at least associated with thunder and storms. In D&D, however, it seems an obvious attack mode once we've dealt with fire and ice, and, naturally enough, it's associated with the dragon that's the colour of the sky.1E

Thursday, 19 August 2021

D&D Monsters: White Dragons

1E

Thursday, 22 July 2021

D&D Monsters: Red Dragons

In D&D, of course, it was originally decided that the five types of chromatic dragon should be distinguished by each having a unique attack, so that green dragons breathe poison, black dragons acid, and so on. Naturally, the most powerful of all the chromatic dragons was going to be the one that breathed fire, fitting the legends on which the broader idea is based.

Thursday, 8 July 2021

D&D Monsters: Green Dragons

In D&D, the basilisk is quite a different creature, and very far from being legless. While the association of poison with serpentine beings make sense, it's not common in depictions of dragons. The D&D idea of certain dragons belching poisonous gas instead of something flammable is likely an original one - something added so that each of the five chromatic dragons had a unique attack mode. And in this case, of course, that's the green dragon, the mid-point in the five-point scale of increasing chromatic dragon power.

Thursday, 1 July 2021

D&D Monsters: Black Dragons

Given that they're right there in the name of the game, dragons are obviously fairly key to D&D. In the 1st edition, they receive more detailed options than other monsters, having eight age categories and three size classes, and a suite of special abilities right from the beginning. Furthermore, there are no less than ten different kinds of true dragon, divided evenly between the good 'metallic' and the evil 'chromatic' species.