Pixies are a form of fairy originally found in the folklore of southwest England, specifically Devon and Cornwall. They are typically more benign than many other fairies, but still mischievous and inclined to cause trouble for humans. In D&D, they were one of four races of fairy-like beings in the original Monster Manual, and seem to be intended as a bit of light-hearted relief, a potentially humorous inconvenience, rather than dangerous monsters to be slain. Of the four originals, they are the only ones to remain in the core monster books for both third and fifth editions.

Pixies are a form of fairy originally found in the folklore of southwest England, specifically Devon and Cornwall. They are typically more benign than many other fairies, but still mischievous and inclined to cause trouble for humans. In D&D, they were one of four races of fairy-like beings in the original Monster Manual, and seem to be intended as a bit of light-hearted relief, a potentially humorous inconvenience, rather than dangerous monsters to be slain. Of the four originals, they are the only ones to remain in the core monster books for both third and fifth editions.1E

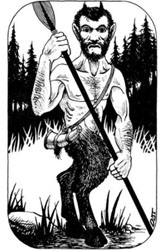

As originally described, pixies look much like elves, except for being only 2'6" (75cm) tall. Or at least, that's what the text says, since the pixie in the picture looks a lot smaller than this. Assuming that the stated figure is accurate, however, it's still a good four inches (10 cm) shorter than a typical two-year-old human child. This makes them the tallest of the four fairy races, and far closer in height to a halfling than, say, a dwarf is to a human. More distinctively, of course, they have two pairs of wings projecting from their back, which look to be similar to those of a dragonfly.

They are highly intelligent, much more so than the average human, but, as one might expect, physically rather weak. Even when they are visible, they are not especially easy to hit, and this probably implies high natural agility as well as them simply being a small target. They seem moderately gregarious, typically being encountered in groups of a dozen or so, although there's no indication of how their society might work. That there's no indication of more powerful individuals among them may well imply an egalitarian culture and it's notable that they all have a fair amount of innate magic. Like most other non-human races in this edition, they speak their own language, which is specifically distinct from that of the sprites, their smaller and more benevolent counterparts.

2E adds that they are vegetarian and nocturnal and have societies based on family ties - which implies that they reproduce like humans do, rather than being some sort of purely magical spirit. Their wings are said to be silvery, and to resemble those of moths.

In 3E, the wings now resemble those of a bee more than anything else. They have the same height as before, but we're told that they typically weigh around 30 lbs (13 kg). This is a typical weight for a 2-year-old human... which, remember, is notably taller than a full-grown pixie. When we add this to the fact that the pixie in the illustration is unnaturally thin by human standards, he would have to be much denser than a human - perhaps due to heavy bones - for this to make sense. Most likely, they're quite a lot lighter.

Most of the detailed numbers provided for the stats are in line with what we had in 1E; the intelligence score remains the same, they're physically weak, but highly agile, and so on. Their acute senses weren't mentioned before, but seem a logical extrapolation. They have, however, shifted to a "good" alignment, and we're told that they go out of their way to fight evil. Rather than just mucking about, as they did before. Some of this may be due to a fusion of the pixie with the sprites of earlier editions since the latter are now a general category of which pixies are a part, rather than a distinct race.

They also live in larger groups than before, with "tribes" of about 50 individuals being common. They now speak the same language as most other fey - and, for that matter, centaurs. A slightly less physical nature is implied by the fact that they're difficult to hurt without using "cold iron" - a term that, in reality, simply means "iron or steel used to make weapons", but, in D&D tends to imply something a bit more special.

Pixies have drastically shrunk in this edition, now being only one foot tall (30cm) - much smaller in comparison to a halfling than a halfling is to a human, and, indeed, smaller than the smallest of the 1E fairy types (the brownie, at 1'6"). Their skin is green, not caucasian, and, no longer cadaverously thin, they have childlike bodily proportions, if a comparatively adult figure. The wings of the one in the illustration resemble those of a butterfly, but we're specifically told that there is some variation in wing-form between different pixies, so the various different forms we've seen up to this point aren't necessarily contradictory.

They have to maintain concentration to stay invisible, which isn't especially hard but isn't quite the innate invisibility of 1E, either. The resistance to regular damage and vulnerability to "cold iron" have both gone, and they're even punier than they were before, as befits their smaller size. A significant change is that they are now no more intelligent than humans, although they retain their inherent charm and heightened senses. They have also abandoned the use of weapons, having previously wielded daggers and been crack shots with bows that were surprisingly effective for their size.

Although pixies shrink in 5E compared with prior editions, all agree that they are much smaller than humans, and they even make halflings look tall. Despite their magical nature, there's nothing to indicate that they aren't physical, biological beings (except possibly the resistance to damage in 3E) rather than some neutral counterpart to demons or angels.

Smaller size does bring some scaling issues with it but, for the most part, nothing that's especially insurmountable, since there are obviously many mammals that are much smaller than pixies. Indeed, the 5E pixie is sufficiently small that, especially with light bones or the like, they might actually be able to fly without absurdly large wings or much in the way of magical assistance - they're considerably smaller than, say, a golden eagle. For that matter, the larger pixies of other editions could technically fly without magic, but they'd need at least a six-foot (180 cm) wingspan to do so, which they clearly don't possess.

The size of the brain does present more of a problem if we're sticking to real-world biology. Scaling issues mean that it must be smaller than that of a human infant, which makes it hard to believe that they'd be more intelligent than a human adult. A certain degree of improved compactness or unusual architecture can get round this - crows, for example, are a lot more intelligent than you'd expect for their size and mice aren't exactly dim by animal standards, but neither are going to write the works of Shakespeare any time soon. So it's likely that, here, real-world neurology is taking a back seat to a fey soul of some kind.

The wings also do present issues other than their size. The actual structure of them isn't much of a problem, with some sort of strong, possibly chitinous, material composing their surface (covered with microscopic coloured scales if they resemble butterflies or moths) and veins running through them just as they do in real insect wings. But it's less clear how they would attach to the skeleton and musculature, both of which they'd need to do in order to function.

The wings also do present issues other than their size. The actual structure of them isn't much of a problem, with some sort of strong, possibly chitinous, material composing their surface (covered with microscopic coloured scales if they resemble butterflies or moths) and veins running through them just as they do in real insect wings. But it's less clear how they would attach to the skeleton and musculature, both of which they'd need to do in order to function.If pixie wings fold as those of insects do - and, in fairness, most of the pictures are ambiguous on this point, so they might not - they require a complex joint at the base to allow multiple different motions, rather than just flapping. The wings seem to originate to either side of the spine in the upper back so, since they can't be anchored to an exoskeleton as they are in real insects, the joint must either be on an extra set of clavicle-like bones below the shoulders, or perhaps connected to the rear part of some of the ribs.

Although small size and a correspondingly light body help, the flight muscles would still need to be large which, per the usual vision of what such creatures should look like, they don't seem to be. For that matter, if the muscles worked like those on insect wings, they'd have to run through where the lungs should be on a mammal, occupying much of the chest cavity. So, while magic might not be required to keep pixies aloft, it probably is more manoeuvrability in the air, or for take-off and landing, perhaps by providing a boost to modified intercostal muscles.

The various unique powers of pixies are, however, all magical, and these don't change much from edition to edition, including invisibility, the ability to cause confusion, read thoughts, create floating lights, and so on. At least in the earlier editions, there's an indication of a reasonably sophisticated culture, considering that at the very least they own (and presumably make) fine tailored clothing and magical weapons. It's clearly one that stays very far apart from typical human society, and therefore pays little, if any, role in the wider history of most game worlds.