In later times, the Romans conflated satyrs with fauns, nature spirits from their own mythology that were part-goat part-man. This is quite different from how early Greek art shows them as looking, but it has become essentially universal in western lore since. Nonetheless, since "fauns" lack the rampant sexuality of satyrs, it was their name that C.S. Lewis used in the Narnia books, and his fauns were far more pleasant than Greek satyrs were said to be. Otherwise, "satyr" has generally been the more common term in fantasy, and that's the term that D&D uses.

1E

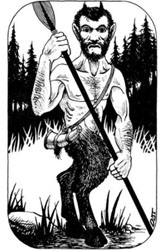

Noting that "faun" is a synonym for "satyr" in the D&D universe, this version has the standard look that satyrs have had since Roman (but not, as noted above, pre-Roman) times. They are basically tanned muscular humanoids that are goat-like from the waist down. They also have horns, which are remarkably small for the amount of damage they are supposed to deliver - similar to a sword.

Noting that "faun" is a synonym for "satyr" in the D&D universe, this version has the standard look that satyrs have had since Roman (but not, as noted above, pre-Roman) times. They are basically tanned muscular humanoids that are goat-like from the waist down. They also have horns, which are remarkably small for the amount of damage they are supposed to deliver - similar to a sword.They are surprisingly skilled fighters - more effective than an ogre - with an armour rating that's superior to that of, say, minotaurs. Given that they don't wear crafted armour (or much else, for that matter) and a thick hide seems unlikely for something with such a humanoid appearance, this presumably represents high natural agility. This is supported by the fact that they can move much more rapidly than humans, and do so with considerable stealth.

Unlike the Greek version, where they are often the butt of jokes, these satyrs have fully human intelligence. They have their own native language, but always speak at least two or three others in addition. Oddly, when they speak Elvish, they can be understood only by one sub-race of elves, not by others, despite there being no other indication that elves speak anything other than a single, mutually intelligible language.

Satyrs are evidently sociable beings, always being found in small groups rather than alone. It's also apparent that they are inherently magical, so much so that other people's spells often don't work on them, and that they are very much in tune with nature.

3E

3E

The 2E version is essentially identical to its 1E predecessor, aside from the addition of an ability to sense heat signatures to their already keen senses. It's also clearer in this version that D&D satyrs are intended to be peaceful and inoffensive, rather than the unrestrained and chaotic (if not particularly deadly) forces of nature that we might expect from their Greek origins.

In 3E, as so often, the changes are more substantial, even though the essential nature of the satyr remains unchanged. Physically, satyrs are less humanoid, with hairier bodies, an obvious mane, pointed ears and a hide almost as tough as chain armour. The horns are much larger than before, resembling those of a ram rather than a goat, but have a more plausible (lower) damage rating.

The 2E ability to see in the infrared has been replaced by a more appropriate low-light vision suitable for starlit nights. They have lost their inherent resistance to hostile magic and can sometimes be found in larger groups than before. They are classified as fey (which, in rules terms, means that they are more focussed on non-combat than combat abilities) and speak the same language as most other fey beings, implying some sort of common origin. Their other languages have been dialled back, no longer being automatically multi-lingual, and not typically speaking Elvish.

Unlike the earlier versions, 3E satyrs are "chaotic neutral", which makes sense for a highly hedonistic race, and there is a note that they are often mischevious. Presumably as a result of their fey nature, they are vulnerable to cold iron, which they were not before. (In the real world "cold iron" is a poetic term that simply means "iron used to make weapons"; in D&D it's generally something more specific and rarer than this).

5E

In some respects, this version returns to something closer to that of the first two editions. The physical appearance is basically the same, although a wide variation in the shape of the horns between individuals is specifically noted. They rely on high natural agility to defend themselves, specifically having skin no tougher than that of a regular human. They are also, it would appear, more likely to wear clothing and their tendency for debauchery is arguably toned down a little.

This time, they do regularly speak Elvish alongside their native tongue - which, of course, is now the same as that of centaurs, among others. They have regained some of their natural resistance to magic, and lost the vulnerability to cold iron. Their senses are now only slightly more acute than those of humans.

Biologically speaking, the only thing that is really unusual about satyrs is that they are exclusively male. Unlike, say, minotaurs, this is something stated in all the editions, and it clearly fits with their mythic origins. Naturally, this raises the question of where new satyrs come from.

Being fey creatures, rather than true 'humanoids', it's conceivable that satyrs are somehow magically created, most likely in some realm like the Feywild. However, given their physicality, it's unsurprising that most sources that state an opinion have opted for a more biological approach. There are two different possibilities here.

Firstly, the females of the species may look sufficiently different that they aren't described as 'satyrs'. This is the option used in 2E, which states that the female counterpart of satyrs are dryads. This makes sense mythically, since, in Greek myth, dryads are woodland nymphs, making them pretty much exactly the feminine equivalent of satyrs. In D&D, nymphs and dryads are different types of being, and satyrs associate with both of them, but either version makes sense.

The alternative, which is used in Pathfinder, is that satyrs are interfertile with many (or perhaps all) types of humanoid and interbreed with them. While perfectly plausible for a being that's inherently magical, this does raise a number of social questions, which bring us to the matter of the satyr's signature power; the use of magical pipes.

The alternative, which is used in Pathfinder, is that satyrs are interfertile with many (or perhaps all) types of humanoid and interbreed with them. While perfectly plausible for a being that's inherently magical, this does raise a number of social questions, which bring us to the matter of the satyr's signature power; the use of magical pipes.Only one satyr in a group has a set of these pipes, although they seem to work for any satyr (but no one else), so it's probably a matter of scarcity of the items rather than some specific skill that only a few individuals possess. These are, of course, pan pipes, named for and associated with the Greek nature god Pan, who really did look like a D&D satyr and often behaved in a similar manner.

The pipes can be used to either make anyone who hears them fall asleep, or to run away in fear. Aside from some minor differences to reflect the way saving throws work, the primary difference between editions here is how long these effects last. This essentially gets weaker with each edition from 2E onwards. In 2E, the effect lasts for several hours, while in 3E the fear effect (the word "panic" actually comes from the god Pan, who had that power) lasts for a minute, and the sleep effect for ten minutes. That's easily long to flee into the woods in the former case, or to quickly frisk slumbering victims for valuables and then make an escape in the latter.

In 5E, however, either effect is unlikely to last for more than a few seconds - considerably less than the equivalent spell cast by a wizard. This is by no means useless, but it's more of a last-ditch defence than anything of wider applicability.

It's the third power, however, that has the greatest ramifications. This is the ability to charm a victim, again, for a decreasing period of time, depending on edition. In most editions, it's stated that this power is used to seduce attractive women.

The extent to which charm magics can be used to obtain sexual favours is a rabbit-hole of its own, but this is clearly the intent in the case of satyrs. This is especially so in Pathfinder, where it seems to be how they reproduce. In 2E, a satyr's charm can last for months, but in Pathfinder, it's eight hours, so that either the child of any resulting pregnancy must somehow be collected by the satyr at a later date, or it has to make its own way in the world. Either raises quite a number of questions of simple practicality, never mind the moral issues.

5E does not describe how satyrs reproduce, but their charm abilities clearly aren't involved, since they don't last anywhere near long enough to seduce somebody. The text description implies that they do have a natural talent for persuading people to engage in revelry, but you'd think the fact that they are half-goat would tend to limit the opportunity for consensual sex with humans - and the way they're described, it's hard to imagine they'd do anything non-consensual. Here, at least, the ethical questions are avoided, even if the biological ones are left open.

In other systems, D&D satyrs would be reflected in highly agile humanoids with an impressive natural charisma and skills that are focussed primarily on dancing, music, and persuasion/seduction. The latter may, of course, be offset by their partially inhuman appearance, although the general opinion seems to be that they are fairly attractive from the waist up. Stealth skills and acute senses may also be appropriate. Their willpower is likely not impressive, but, in many systems, this can also be dealt with by giving them specific drawbacks/disadvantages that reflect a weakness for wine and women.

Because the duration of the pipe effects has changed so massively between D&D editions, it's hard to say how they would be handled, although mirroring existing spells would be the simplest, and probably safest, options. After all, in most D&D editions, they are no more effective than equivalent wizard spells, and in 5E, they are actually less so.

No comments:

Post a Comment